The Rise and Fall of Groundwater: Monitoring in the Columbia Basin shows variability in response to drought conditions.

July was the hottest month ever recorded on Earth and set the stage for rampant and worsening drought impacts across Western Canada. Dry creek beds, stranded fish, parched crops, scarce feed for livestock, severe wildfires, the list goes on.

As of August 17th, the Province of BC is reporting that over 80% of water basins across British Columbia remain at a Drought Level 4 or 5 (see Drought Map). Alarmingly, the latest update reveals a significant jump in the number of watersheds at Drought Level 5 from 32% to 56%. This means over half of B.C. watersheds face “almost certain” negative impacts.

This growing crisis points to the need for more comprehensive water monitoring to help support and direct proactive water management.

Living Lakes Canada’s Columbia Basin Groundwater Monitoring Program is collecting long-term data on groundwater levels to track annual and seasonal changes. Many municipalities and rural property owners rely on groundwater, yet little is known about how climate and other impacts like land use are affecting the water underground.

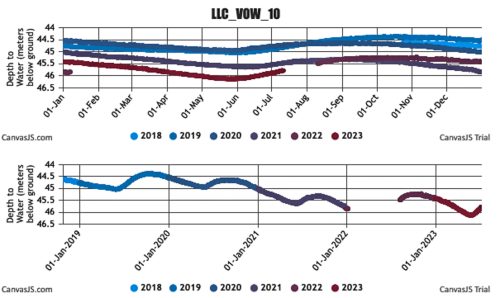

The program now has some wells with up to six years of data, providing us with information on how aquifers are responding to surface events.

- This spring, water levels in some wells were the lowest recorded to date.

- In one of the wells, we’ve seen a decreasing trend over the last six years.

- In other wells, peak water levels occurred earlier this year than in previous years. This corresponds with this year’s smaller winter snowpack and unseasonably early snowmelt.

In June, one of the wells located in Windermere had the lowest water level recorded in the last 5 years, following a decreasing trend since 2018 (see the graph). While the data shows that the lowest water levels typically occur in June, groundwater levels reach their highest point around October/November. This shows the seasonal variability of this 160 foot deep well in an aquifer composed of clay and gravel.

Notably, the program’s data is showing that water levels in aquifers higher up in the mountains peak at different times than valley bottom aquifers. This means that conditions at one select well aren’t necessarily representative of groundwater conditions across an entire region.

For example, in contrast to the Windermere well, another well located near Silverton, which is approximately 300 feet deep in bedrock material, has highest water levels occurring in the spring around April/May, and the lowest levels in fall around October/November.

Site-specific information is essential to inform decision-making for water security.

“A good analogy for this is to think of a bank account where you monitor both cash flow and a monthly total. The water level in an aquifer is similar to the net balance in the account, and recharge to and outflow from the aquifer is equivalent to cash flow,” described Remi Allard, a consulting hydrogeologist with McElhanney in Cranbrook and an advisor to the Living Lakes Canada groundwater program.

“Recharge to aquifers in the Kootenays occurs mainly during freshet but is also derived from infiltration of precipitation. If recharge is less than normal as a result of low snowpack and/or less than normal precipitation, but groundwater use remains constant, then the water balance in an aquifer can be negatively impacted,” he said. “In short, you have to measure things in order to manage them.”

In an attempt to better manage groundwater use, the Government of BC introduced a new licensing system in 2016 requiring commercial users of groundwater to apply for a licence by March 2022. Now with this summer’s unprecedented drought, the province has started to cut groundwater access to unlicensed water users and the results are proving precarious for farmers and other commercial operators.

As Mike Wei, the former provincial program lead for groundwater and deputy comptroller of water rights, and current consultant, recently told The Tyee, “I did not expect this summer’s drought to so quickly shine the spotlight on the water rights issues.” Wei also advises the Living Lakes Canada groundwater program.

The program partners with well owners to establish a cost-effective network of Volunteer Observation Wells across the Canadian Columbia Basin region. This work complements the monitoring done by the Provincial Groundwater Observation Well Network. Although there are over 230 active observation wells in the provincial network, there are only 6 wells in the Columbia Basin. The Living Lakes Canada program has established and is currently monitoring 32 Volunteer Observation Wells across the region.

This year, some of the provincial monitoring wells within the Basin have also shown their lowest ever water level measurement to date, including wells in Wasa and Jaffray. This data can be seen on the recently released Groundwater Conditions tab on the BC Drought Portal. The map is a valuable resource, and shows the unmonitored terrain in the provincial network.

Across Canada, aquifers vary in size and complexity. In the mountainous Columbia Basin, many aquifers are small and fragmented. Each responds differently to climate conditions and water usage demands. The Living Lakes Canada program is addressing the gaps in groundwater monitoring across this complex landscape by continuing to collaborate with water supply operators, First Nations, municipalities, ranchers, land trusts, post-secondary institutions and private landowners to collect and share groundwater level data.

Roberta Schnider, Area G Director with the Regional District of East Kootenay, is an advocate for expanded groundwater monitoring as climate and other impacts intensify.

“I have climate concerns, primarily around how surface water is being impacted and the pressure this puts on communities’ water supply,” said Schnider. “For example, the intake for the Edgewater community’s water system is Baptiste Lake, which is also seeing more development. I want a secondary water source, and aquifer water is much cleaner, requiring less treatment and maintenance. There’s a real need for improved groundwater monitoring as communities start turning to groundwater for a reliable source of drinking water.”

We need your support to continue the groundwater monitoring program. Make your positive impact on sustainable water management today!