A changing landscape: High elevation fieldwork at Talus Lodge

The early arrival of spring in the mountains is often a welcome sight, but it also spells climate change. According to the June 15 snow survey report from the BC River Forecast Centre, there is no measurable snow remaining compared to normal conditions due to the rapid thaw of the mountain snowpack. Without the steady flow of water from melting snow, the provincial government has issued warnings about increased risk of drought across British Columbia throughout the summer months. As of July 25th, 21 out of 34 regions were classified at Drought Level 4 or 5, with negative impacts on ecosystems and communities rated as “likely” or “most certain”.

How will climate change continue to impact alpine headwaters and what does this mean for human communities and the ecosystems that rely on this water source? Living Lakes Canada’s High Elevation (HE) Monitoring Program aims to help answer these questions, and there’s a way you can help too.

After a successful pilot year in 2022, the HE Monitoring Program is expanding throughout the East and West Kootenays, with six stream monitoring sites and nine lake monitoring sites, including the Talus Lakes. On a recent fieldwork trip to Talus Lodge, the HE team witnessed the local impact of climate change.

Situated on the Continental Great Divide, the Talus Lodge stands at an altitude of 2,300 metres amongst a scattering of small alpine lakes. This year, the ice melted off the lakes three weeks earlier than usual, making it the earliest ice-off recording of the last six years. Anecdotally, the lodge’s staff spoke about enjoying early summer ski turns last July, whereas this July the slopes are bare.

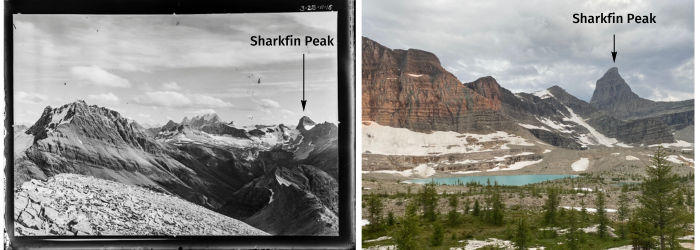

An archival photo from 1916 shared with the HE team shows a glaciated basin behind Talus Lodge. Today, there are little remnants of this glacier.

Earlier snowpack melt and lake ice-off, increased glacial melt, and warmer temperatures are changing alpine landscapes. Furthermore, new research shows that as the climate warms, extreme rainfall events are projected to increase at high altitudes in the Northern Hemisphere. Associated hazards, including floods, landslides and soil erosion, further threaten to alter alpine environments and the watersheds they’re part of.

During a recent trip, the HE team installed monitoring equipment at both the north and south Talus Lakes. This included level loggers and barometric loggers near the shore to measure changes in water level. From the start to the end of the ice-free season, pendants are suspended between an anchor at the deepest part of the lake and a buoy floating at the surface to measure changes in light and water temperature. Various lake parameters were collected including, but not limited to, dissolved oxygen, pH, total algae and turbidity (water clarity). Photos of the area were captured and observations of resident flora and fauna were uploaded to iNaturalist for species identification.

This work will help generate baseline data to better understand how Talus Lakes are seasonally influenced in response to various climate factors. Monitoring may help Talus Lodge – as well as other participating Backcountry Lodges of BC members involved in the program – to better understand how climate change is impacting their local water supply required for operations.

Over the long-term, high elevation monitoring will inform water management and decision-making, and support climate change adaptation. All the data collected through this program is housed on the publicly accessible Columbia Basin Water Hub database.

In partnership with the Alpine Club of Canada, the HE Monitoring Program has also launched a citizen science project on the popular iNaturalist platform.

Anyone is welcome to contribute by joining the High Elevation Monitoring Program – Living Lakes Canada project on iNaturalist and uploading pictures of flora and fauna they spot while recreating within the HE Program’s active monitoring locations. These locations include Kokanee Glacier Provincial Park, Fletcher Lakes, Fishermaiden Lake, Macbeth Icefields, Ben Hur Lake and Shannon Lake in the West Kootenays and Talus Lakes in the East Kootenays. This citizen science project will create a valuable inventory of plant and animal species available to the HE team, as well as other researchers.

Learn more about this project and how to participate by visiting the HE Monitoring Program page.

Looking for another way to support the critical work underway by the High Elevation Monitoring Program? Your generous donation will help us gain a comprehensive and science-based understanding of alpine headwaters.

For questions, please contact Heather Shaw, High Elevation Program Manager, at heather.shaw@livinglakescanada.ca.