Mapping the way to restore an old sawmill site

Empowering community groups with essential mapping of watersheds

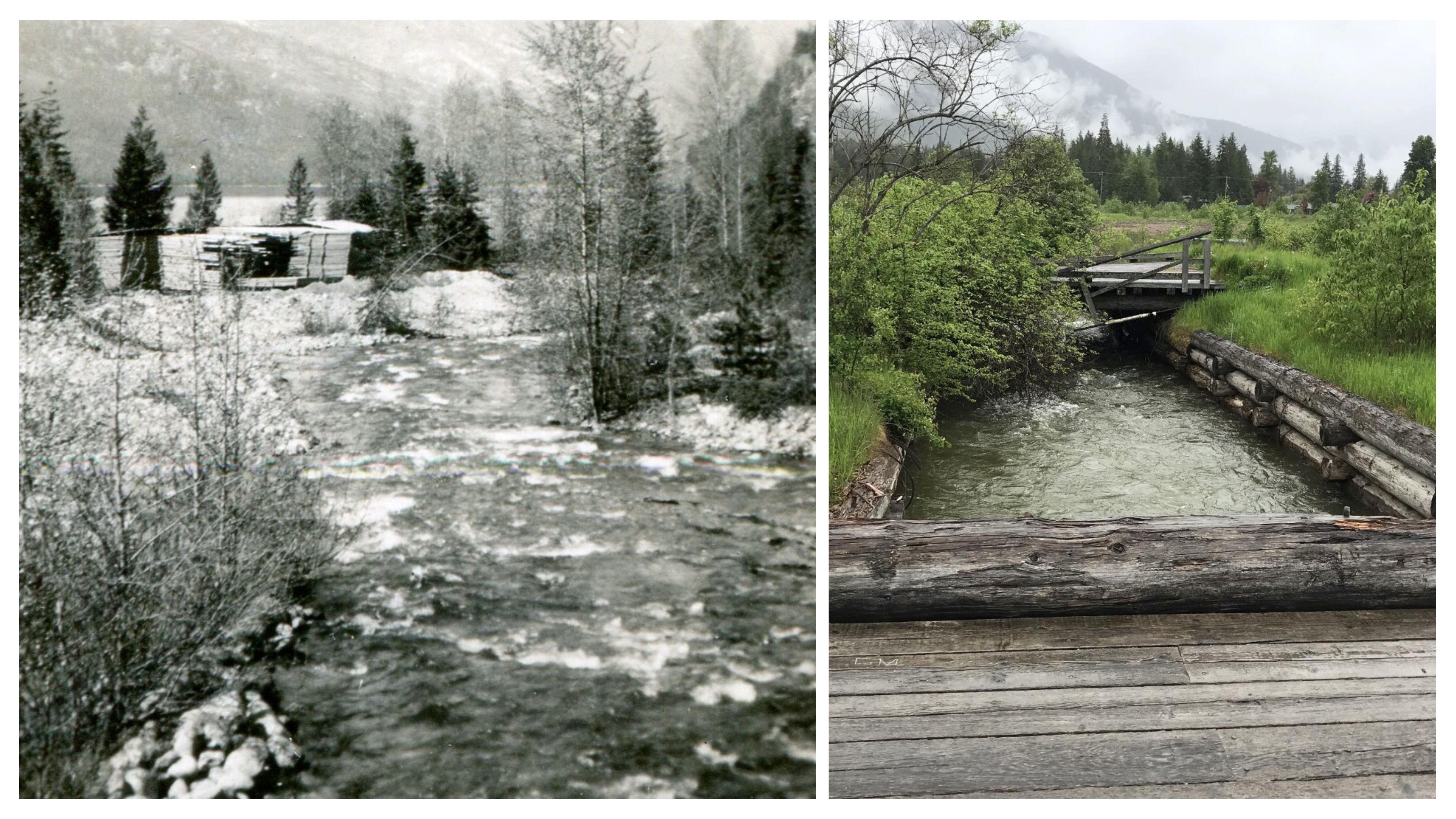

Over 60 years ago, Springer Creek looked a lot different. Abundant Bull Trout and Kokanee Salmon travelled up and down its meandering waters and a rich diversity of trees and shrubs lined its banks.

With the arrival of logging to the Slocan Valley in the early 20th century, one sawmill set its sights on the mouth of Springer Creek. Once a thriving aquatic and terrestrial ecosystem, the lower portion of Springer Creek experienced a steep ecological decline with the sawmill construction. The impacts are still visible today. With the support of a community mapping program, one summer student has been working with a local water stewardship group to tell the story of Springer Creek and guide future restoration efforts.

In partnership with the Selkirk Geospatial Research Centre at Selkirk College, Living Lakes Canada offers a free mapping program in the Columbia Basin. Through this program, GIS co-op students develop easy-to-interpret and engaging maps to help communicate complex watershed information and grow a better understanding of local watersheds. In 2023, two students worked with eight different organizations across the Basin. The Slocan Waterfront Society requested a map to support their efforts in restoring fish passage to Springer Creek.

During the 1960’s construction of the Triangle Pacific Sawmill, artificial mechanisms were introduced to change the natural course and control the flow of Springer Creek. A concrete culvert was installed approximately 100 metres from where Springer Creek drains into Slocan Lake, blocking fish from travelling upstream. Without a channel to swim up, Kokanee Salmon are no longer able to access critical spawning grounds. Bull Trout have also all but disappeared from the creek since they depend on Kokanee Salmon as a food source.

The rise of the sawmill also witnessed the fall of the creek’s riparian zone (defined as the area of land that borders waterways). Riparian areas are critical for the health of surrounding ecosystems. They provide habitat and food for wildlife, stabilize creek banks and prevent erosion, maintain water quality by filtering out excess nutrients, and regulate water temperature by providing shade.

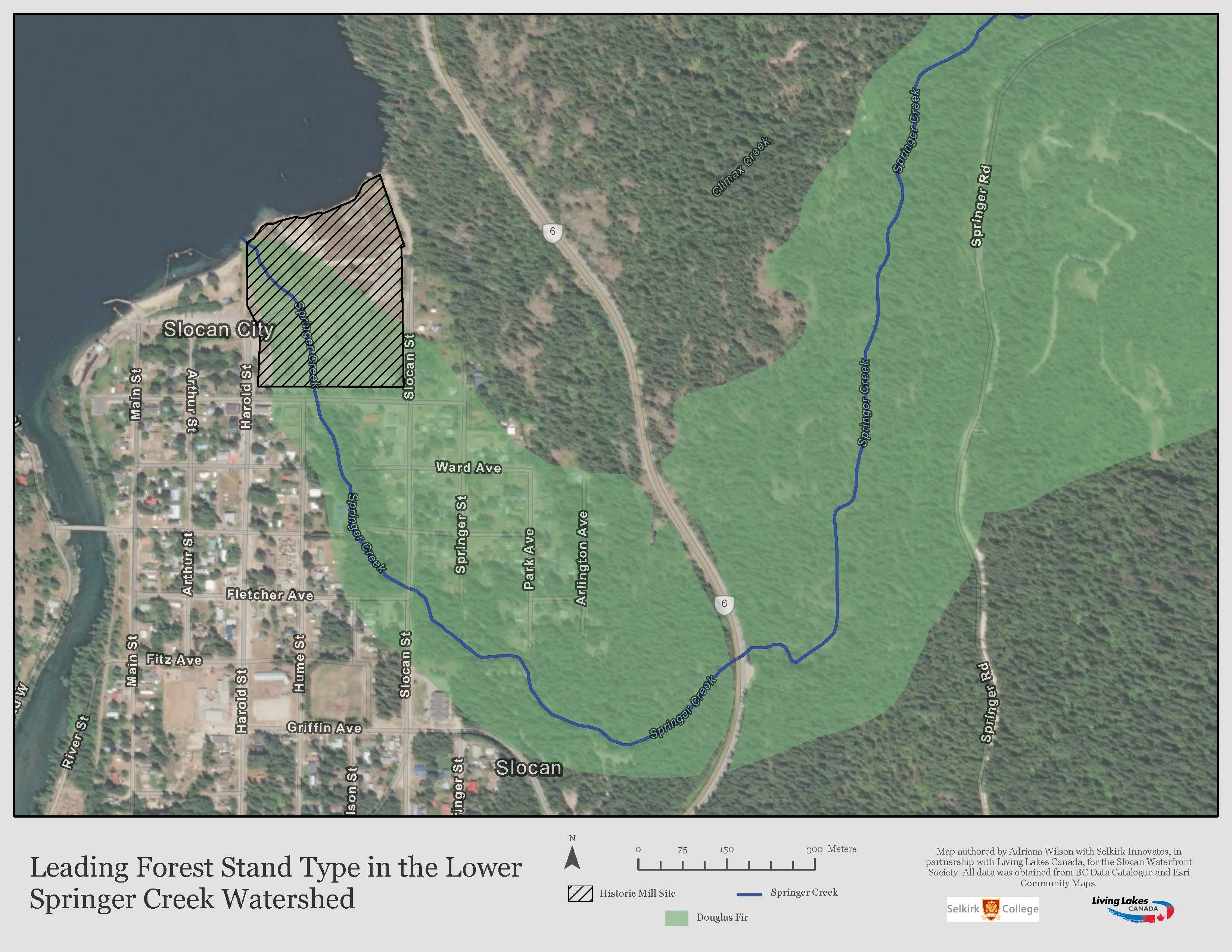

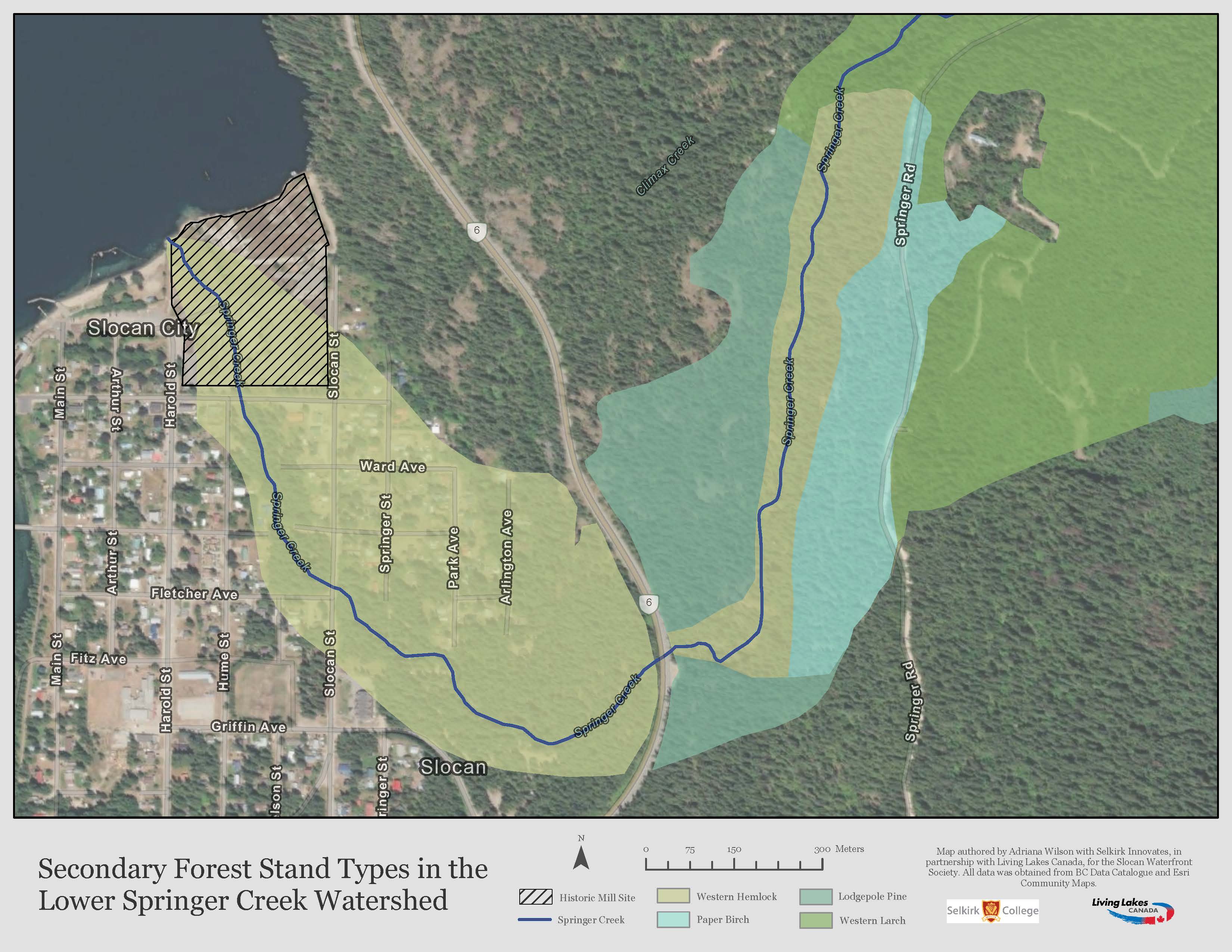

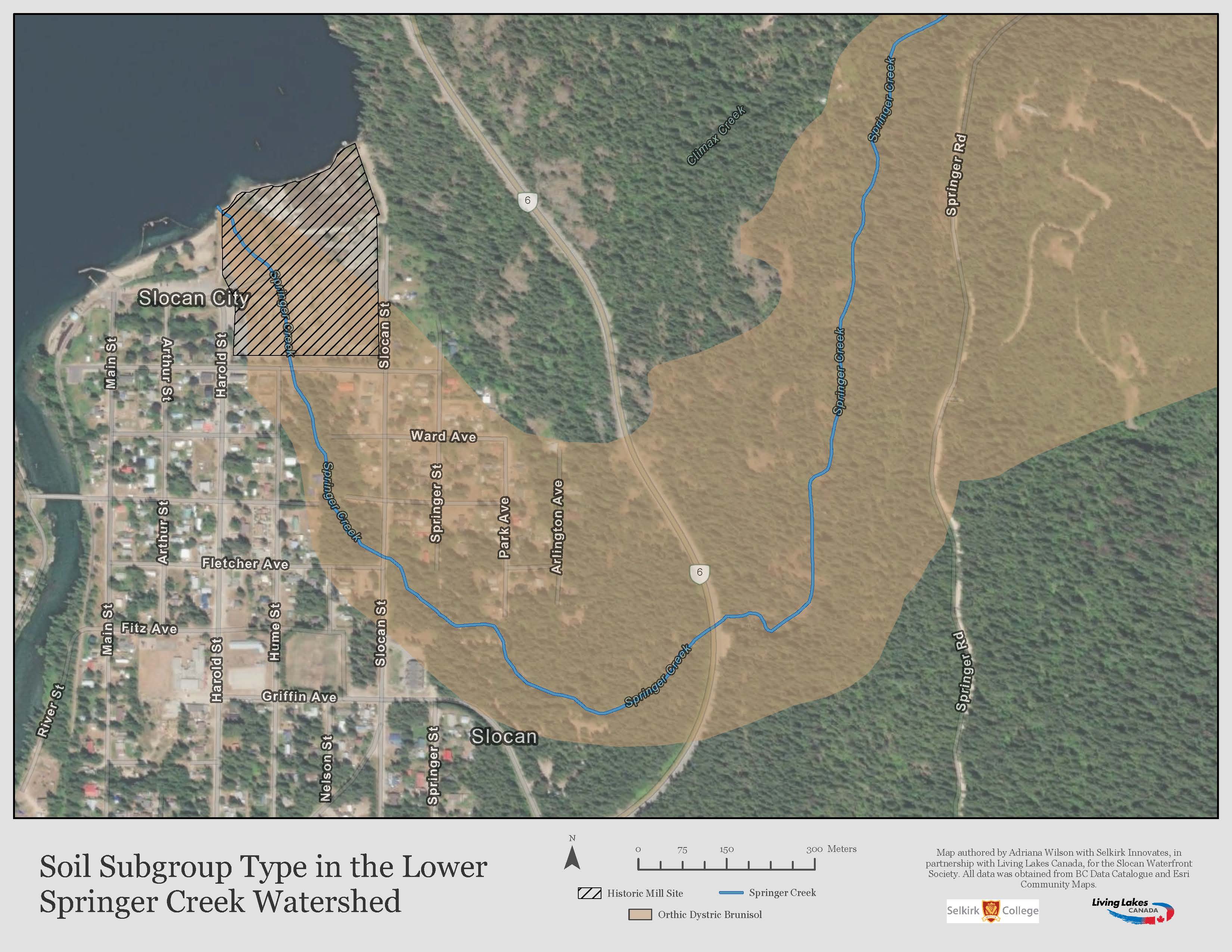

One of the first steps in any restoration process is to better understand the current environmental conditions — and this is where the mapping program comes in. Over the past summer, Adriana Wilson, a GIS co-op student with the Selkirk College Geospatial Research Centre, mapped the tree species and soil type present in the Lower Springer Creek Watershed. As seen in the maps below, the dominant tree species is Douglas Fir. Other tree species living in the watershed include Western Larch, Paper Birch, Western Hemlock, and Lodgepole Pine. Brunisolic soils was identified as the main soil order in the area, typical of forested areas.

A StoryMap, a web-based application that integrates maps, text and other multimedia to create more interactive content, was developed using the tree and soil maps along with archival and current day images and historical information. This online map provides an informative, engaging and accessible narrative of Springer Creek.

In 2013, the Triangle Pacific Sawmill officially closed and the City of Slocan purchased the mill site in 2020. The ownership transfer “sparked conversations about how the land could be best repurposed to benefit the community”. The Slocan Waterfront Society has been involved in these conversations as an advocate for the restoration of Springer Creek.

Adriana reflected on her experience mapping the creek: “While I started the internship hoping to get geospatial mapping experience, I left with so much more. Alongside developing a valuable and diverse skill set, I gained an understanding and appreciation for how maps can help stewardship groups understand their local watersheds like Springer Creek.”

“Our relationships with waterways and water sources within our communities are of profound importance,” said Robert MacQuarrie, researcher and instructor with Selkirk Innovates, Geographic Information Systems. “Geographic technologies provide a way to present water data through visually engaging and easy-to-understand maps.”

As part of Living Lakes Canada’s Action for Healthy Watersheds program, the mapping program accepts applications from stewardship groups, local and regional government or Indigenous communities. For groups unsure about their mapping opportunities, the program offers free consultations. The 2024 mapping program will begin accepting applications in the upcoming spring.

“The partnership between Selkirk College and Living Lakes Canada provides groups with access to technology, costly software and expertise to accomplish their mapping projects,” said Maggie Finkle-Aucoin, GIS and Database Coordinator with Living Lakes Canada.

Thank you to all the organizations that participated this year including the Slocan Waterfront Society, Friends of Kootenay Lake Stewardship Society, Arrow Lakes Environment Stewardship Society, Heddlestone Village, Slocan River Streamkeepers, Blaeberry West Residents, Wasa Lake Improvement District and Rossland Streamkeepers.

For more information about the program, please contact Sophie Gonthier, Lakes Program Coordinator, at sophie@livinglakescanada.ca.